This Guest Director’s Blog is by Mark Walton, PhD.

He is a senior research scientist at WaNPRC in the Neuroscience core. We welcomed his timely thoughts in a climate in which it’s valuable to understand the importance of animal research in advancing human and animal health.

In January of 2002, my first child, a son, was born. When he was still only minutes old, the doctor handed me our newborn child and said, “Here’s your son.” The joy I felt in that moment was beyond description, and I couldn’t help speculating about what the future would hold. What sort of life would he lead? Would I be up to the task of preparing this utterly helpless person for the independence of adulthood? I desperately hoped that he would one day find a career path that he would find fulfilling. I thought, too, about the fact that this newly arrived human being that had been entrusted to our care would likely outlive us by at least a couple of decades. I hoped that he would one day find love so that he would always have a family that he could trust.

As I held him in my arms for the first time, I could see that his skin had a bluish tint, but I wasn’t worried at first. We had been warned that newborn babies often take a little while to get their natural color, as their delicate little lungs begin to supply oxygen for the first time. I was so engrossed in the tiny miracle that rested in my arms that I failed to notice the growing concern that must have shown on the faces of the medical professionals that surrounded me. My own concern began to grow slowly, an empty feeling in my gut as I waited for the bluish tint to his skin to turn pink. Instead, his color worsened until a nurse gently took him from me. Soon a doctor explained to me that our son was having trouble breathing because his lungs were not as mature as they should have been. My wife and I were told that he had been taken to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), where they would help him to breathe. The technical term for this is respiratory distress syndrome.

That night my wife and I somehow managed to get to sleep. In the morning, the doctor told us that our baby had a “rough night.” She explained that normal lungs produce something called surfactant, which essentially keeps the lungs from sticking together when we exhale. To understand the need for surfactant she asked us to imagine trying to inflate a balloon that was wet on the inside. Our baby’s lungs, she said, were not mature enough to produce the surfactant that he needed. During the night, when he tried to inhale, one of his lungs stuck together. This ripped a hole in the lung, which caused it to collapse.

I listened, doing my best to show a strength that I didn’t feel. I knew this would be even worse for my wife, who was listening to the same horror story after giving birth to a baby. After the doctor finished, I stepped out into the hallway. The moment the door closed the fear that I had so carefully hidden came pouring out like flood water from a collapsed dam. In the hallway of the maternity ward – which should have been filled with joy – I sank to the floor, unable to stand. I wondered if our son was going to die without being held by his mother even once. I must have been quite a sight: a six-foot-three man crying uncontrollably on the floor while new parents walked past me with their healthy babies.

Later that morning, my wife and I were told that we could go to see our son. The doctor led us to the NICU but paused before opening the door. “I need to tell you what you are going to see,” she said. “Your son has a little ‘boo-boo’.” She used those words to describe what turned out to be a hole in our baby’s chest, into which a tube had been inserted. I remember watching the little drops of our child’s blood moving back and forth inside the semi-transparent tubing.

I couldn’t help wondering what our tiny son, just one day old, thought of the world that he’d entered. To him, it must surely be a place of endless pain and suffering. He hadn’t known comfort or love, except for those few precious minutes, in my arms. I would have done anything – even volunteered to be tortured to death – to take away his suffering and heal him.

In the days that followed, our son received an artificial surfactant, developed through years of research. It worked like a miracle. Soon, we were able to bring him home. That was 2002. Today he is a college student with a brilliant mind, studying astrophysics. He got married last summer, and I can honestly say that I have never seen a happier couple.

This miracle happened because of decades of animal research. Thanks to this research, scientists and medical doctors know a lot about how lungs work. Some of the most important work was done by studying pig lungs – experiments that could not have been performed on humans. Thanks to medical research involving animals, scientists learned the crucial role that surfactants play, and they learned how to make the artificial version that saved our son’s life. Before trying it on human babies, scientists first tested it on prematurely born monkeys. All medical treatments undergo this critical phase of testing, ensuring that new treatments are safe before they are given to humans – or, more personally, our children.

In 1963, President John F Kennedy’s newborn son tragically died of the very same problem that nearly killed our son. At that time, medical science had not advanced enough to save him. Medical research, including research involving monkeys, is the only reason that our son survived. For us, this is not a political issue; it is the difference between life and death. Yet as I write this, countless other families are not so fortunate. At this very moment, thousands of parents are watching helplessly as their children suffer and die of diseases that we have yet to treat. For them, the horror that I felt for a few short days will become an emotional wound that never heals.

It’s normal in a democracy for well-meaning, patriotic people to disagree about many things. The need to spare our fellow human beings the indescribable horror of losing a loved one should not be one of them. If there is one thing that we all should agree on, it is that we must support medical research. Every single person reading these words should remember that one day it might be your life that hangs in the balance, or the life of someone that you love. It is my great hope that we continue to support medical research so that an effective treatment will be found before that day comes for your family.

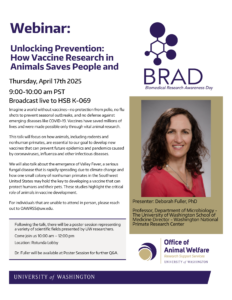

WaNPRC Director Dr. Deborah Fuller today welcomed Dr Raimon Duran-Struuck as a core faculty member of the Washington National Primate Research Center. Dr Duran-Struuck is the Chair and a Professor in the UW Department of Comparative Medicine (DCM).

WaNPRC Director Dr. Deborah Fuller today welcomed Dr Raimon Duran-Struuck as a core faculty member of the Washington National Primate Research Center. Dr Duran-Struuck is the Chair and a Professor in the UW Department of Comparative Medicine (DCM). WaNPRC’s Interim Assoc. Director for Research, Kristina Adams Waldorf collaborated on a four-part series with other researchers in

WaNPRC’s Interim Assoc. Director for Research, Kristina Adams Waldorf collaborated on a four-part series with other researchers in  Neuroscience core scientist Amy Orsborn published a

Neuroscience core scientist Amy Orsborn published a