After 35 years with the Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC) and the University of Washington, Dr. Randall (‘Randy’) Kyes, Unit Chief of the Center’s Unit of Global Programs, Research Professor in the Dept. of Psychology, adjunct in the Depts. of Global Health and Anthropology, and Director of the Center for Global Field Study, will retire at the end of December 2025. His career leaves behind a legacy of science, service, and compassion that spans continents and generations.

From the tropical forests of Indonesia to the mountains of Nepal, Kyes has devoted his entire professional life to building lasting international partnerships and training thousands of students and professionals to care for the natural world and one another.

“Everything we do to the environment affects our own health,” he said. “If we can improve environmental health, we improve human health too.” That belief was the foundation for decades of work connecting people and ecosystems across the globe.

When asked to look back, Dr Kyes seems amazed at how it all began. In 1989, during his postdoc at Wake Forest School of Medicine, he met an Indonesian scientist, Dondin Sajuthi, who mentioned a small island where long-tailed macaques were being released to establish a breeding population. “He told me the folks at the University of Washington were looking for someone to monitor how the monkeys were doing,” Kyes recalled. “I went the next summer to conduct a population survey of the macaques, and that was it. Everything started from there.”

That was Tinjil Island, Indonesia. In 1991, Dr Kyes led his first field course there, an experience that would grow into a global model for collaborative field training. Over the next three decades, he and his longtime collaborators, both international and domestic, led 148 field courses in eight countries for nearly 2,900 participants representing 20 nations.

“Our goal was always to help local people build their own capacity to manage their environment and health,” he said. “These programs were never about us showing up to teach and then leaving. They were about partnership and long-term collaboration.”

“Our goal was always to help local people build their own capacity to manage their environment and health,” he said. “These programs were never about us showing up to teach and then leaving. They were about partnership and long-term collaboration.”

That philosophy extended well beyond university students. Around 2000, while working in a rural Indonesian village coping with crop-raiding monkeys, Dr. Kyes and his team met with village leaders to discuss ways to help mitigate the conflict and protect the endangered animals. “They were grateful, but they said, ‘We’re set in our ways. You should talk to our kids before they are, to help them appreciate the need to protect these monkeys?’”

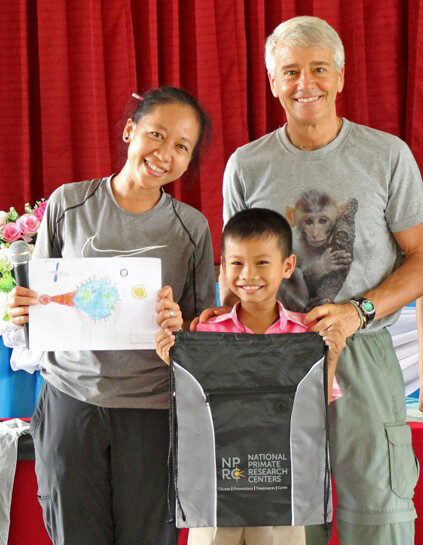

He and his colleagues took that advice to heart. The following year they launched their first K-12 outreach program, combining lessons on wildlife conservation with art and health activities. Over the next 25 years, that grew into 181 outreach programs reaching more than 10,000 children across eight countries.

“One of my favorite moments came years later,” he said. “Two young women from that same village joined one of our field courses and told us they’d been third graders in our very first outreach session. Seeing that full circle, kids who grew up to become conservation students – that’s the kind of impact you hope for.”

Asked what kept him going through the endless travel, the weather, and the occasional political unrest, and he’ll point to his students. “Watching them discover the field, that spark when they realize they can do this work, is what I’ll miss the most,” he said.

The field courses, which combine research, cross-cultural exchange, and a dose of physical endurance, are intentionally small, he said. “We’re often in remote, challenging places. You learn to improvise, listen, and collaborate,” he said. “It’s not just about training and data collection. It’s about experiencing the world first hand, while appreciating the similarities across all cultures.”

The field courses, which combine research, cross-cultural exchange, and a dose of physical endurance, are intentionally small, he said. “We’re often in remote, challenging places. You learn to improvise, listen, and collaborate,” he said. “It’s not just about training and data collection. It’s about experiencing the world first hand, while appreciating the similarities across all cultures.”

Running global programs for decades meant confronting real-world challenges. Some years were canceled due to political unrest or natural disasters. In 2015, an earthquake and landslide wiped out an entire Nepali village where Dr. Kyes and his colleagues had worked for more than a decade. “We knew those families,” he said quietly. “It was heartbreaking. But we went back. You don’t just walk away from people who’ve become part of your life.”

Those long-term connections remain what he values most. “I’ve stayed in people’s homes, watched their kids grow up,” he said. “That’s the reward, those friendships that cross borders.”

![]()

![]()

![]() He’s also quick to credit his wife and colleague Dr. Pensri (‘Elle’) Kyes, who has been part of the collaborative team since 2010 and became a Research Scientist with the Primate Center in 2014. She has been integral in helping run education programs and coordinate field logistics. “The outreach activities in many of our program countries wouldn’t exist without her,” he said. “She has an incredible way of connecting with communities and the children.”

He’s also quick to credit his wife and colleague Dr. Pensri (‘Elle’) Kyes, who has been part of the collaborative team since 2010 and became a Research Scientist with the Primate Center in 2014. She has been integral in helping run education programs and coordinate field logistics. “The outreach activities in many of our program countries wouldn’t exist without her,” he said. “She has an incredible way of connecting with communities and the children.”

Kyes’ work has always focused on empowerment. Every field course is designed and led with local partners who provide lectures, field expertise, and cultural context. That also helped create a network of alumni, many of whom now run their own training programs.

“I’ve been incredibly fortunate,” he said. “Few people get to do work that means so much to them personally and that connects them to so many others. It’s been the privilege of my life.”

Even as he retires from his formal UW roles, he hopes the programs will continue. “What I’d really love,” he said, “is to see the next generation keep this momentum going. If we’ve done our jobs right, they already are.”

By the Numbers (1990–2025):

- 35 years with the WaNPRC

- 148 field courses in 8 countries

- 2,894 participants representing 20 nations

- 181 outreach programs for 10,272 K–12 students

- 30+ years of continuous collaboration in Indonesia

- 20+ years of continuous collaboration in Nepal and Thailand

- 10+ years of collaboration in Bangladesh, China, India and Mexico

Related Links:

- Taking a Walk on the Wild Side. (1998)

- The Center for Global Field Study: Training environmental stewards worldwide. (8 Oct 2009)

- UAV Technology Demonstrated for Potential Application in Conservation Biology and Global Health. (Aug 2014)

- Animals and Your Health at PAWS on Science. (2014)

- Center Scientists Bring STEM-Based Educational Field Course to Native American Youth. (2014)

- Monkeying Around in Remote Indonesia. (24 sept 2015)

- From Crop-raiding Monkeys to Political Unrest: UW’s Randy Kyes Embarks on 100th Field Course. (21 July 2016)

- Randy Kyes Leads 100th Field Course, Reflects on A Program Nearly 30 Years in the Making. (2016)

- UW on the Mekong River with Dr. Pensri (“Elle”) Kyes. (2017)

- Conservation Leaders of Tomorrow Look to Yesterday: 20 Years of Community Outreach Education at the Tangkoko Nature Reserve, Indonesia. (2019)

- International Field Course Held in Indonesia and Led by UW Professor Ends After 30 Years. (29 Sept 2022)

- An Epic Celebration Three Decades in the Making… But it Almost Didn’t Happen. (2022)

- Highlights from the Himalayas. (2024)

- WaNPRC’s Global Conservation, Education and Outreach Unit Marks 25 Years of Field Training in Tangkoko. (2025)

- New Leader for Global Programs Named. (2025)

Researchers from the Washington National Primate Research Center

Researchers from the Washington National Primate Research Center  A new national survey on public attitudes toward animal research indicates that trust, and communication based in facts, play a huge role in acceptance for the work. The survey identified veterinarians (81%) and scientists (77%) as the most trusted sources of information.

A new national survey on public attitudes toward animal research indicates that trust, and communication based in facts, play a huge role in acceptance for the work. The survey identified veterinarians (81%) and scientists (77%) as the most trusted sources of information.

Vaccines access is becoming a national checkerboard of availability, with wide gaps between where they’re available and where they’re not.

Vaccines access is becoming a national checkerboard of availability, with wide gaps between where they’re available and where they’re not. The NIH and FDA efforts to shift away from animal testing, promoting “new approach methodologies” (NAMs) like AI, organoids, and organ-on-a-chip systems are not finding unanimous support in the scientific community. The goal is to improve research efficiency, lower costs, and reduce harm to animals. While some scientists support the move as overdue, others warn that NAMs can’t yet replace animal models in many areas, like cancer and radiation research. Experts are also concerned about the speed of implementation and the risk of compromising scientific rigor. The shift comes amid broader federal cuts to basic science funding, raising doubts about how far these changes can be effectively realized.

The NIH and FDA efforts to shift away from animal testing, promoting “new approach methodologies” (NAMs) like AI, organoids, and organ-on-a-chip systems are not finding unanimous support in the scientific community. The goal is to improve research efficiency, lower costs, and reduce harm to animals. While some scientists support the move as overdue, others warn that NAMs can’t yet replace animal models in many areas, like cancer and radiation research. Experts are also concerned about the speed of implementation and the risk of compromising scientific rigor. The shift comes amid broader federal cuts to basic science funding, raising doubts about how far these changes can be effectively realized. A new study led by researchers at the Washington National Primate Research Center shows that applying electrical stimulation to the brain within an hour of stroke onset may significantly reduce brain damage. The findings, published July 21, 2025, in Nature Communications, advance stroke intervention research and suggest a potential new path for early treatment in humans.

A new study led by researchers at the Washington National Primate Research Center shows that applying electrical stimulation to the brain within an hour of stroke onset may significantly reduce brain damage. The findings, published July 21, 2025, in Nature Communications, advance stroke intervention research and suggest a potential new path for early treatment in humans.