A new study from researchers at the WaNPRC and Seattle Children’s Hospital offers clues about how viral infections during pregnancy might affect a developing baby’s brain — possibly linking early changes to the development of neurological or psychiatric conditions later in life.

Scientists studied the effects of two viruses — influenza A and Zika — on fetal brain development in pregnant pigtail macaques. Their focus was on a vulnerable area of the brain that’s vital for communication between different brain regions and is still developing late into pregnancy.

In some of the fetal brains, researchers found unusual changes in cells called astrocytes — the brain’s support cells. These altered astrocytes were filled with tiny granules and stood out under the microscope. The researchers dubbed these cells “inclusion cells” because of the grainy material packed inside them.

These inclusion cells showed signs of stress and self-digestion. Nearby immune cells in the brain also appeared activated, suggesting the brain was responding to some kind of injury. These changes were more common when the mother had been infected just a few days to up to three weeks. But they weren’t seen with longer or much shorter infection windows — or in brains affected by other types of injuries, like oxygen deprivation.

The viruses also didn’t seem to be infecting the fetal brain directly. Instead, the brain may have been reacting to inflammation or immune signals from the mother’s body — not the virus itself.

These changes didn’t cause visible birth defects, but they may represent subtle, early damage that could affect brain wiring or development. This is important because many conditions like autism, epilepsy, or developmental delay don’t always show obvious signs on brain scans but may be linked to very early injuries.

The study raises questions about whether a mild or unnoticed infection during pregnancy affects a baby’s brain in ways that only show up years later. And could a better understanding of these mild injuries help us prevent or treat neurodevelopmental disorders?

“A healthy brain at birth is the foundation for a child’s ability to develop to its full potential,” said Dr. Adams Waldorf, a Professor at UW Medicine and lead researcher on the study. “If we understand how these kinds of subtle fetal brain injuries begin, we can figure out how to prevent them in the first place.”

More research is needed — especially in humans — to answer those questions. But for now, their findings add to growing evidence that maternal health and immune responses during pregnancy can play a powerful role in shaping brain development long before birth.

You can read the full report in Acta Neuropathologica Communications.

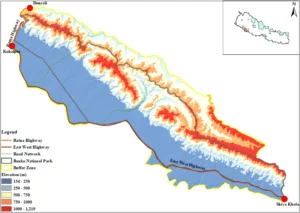

The researchers didn’t stop at counting the accidents. They wanted to understand where and why they were happening. Using maps, field surveys, and computer models, they identified three major danger zones on that road. These hotspots were responsible for more than 60% of all wildlife collisions. They also learned that accidents happened more often in the autumn, when animals are more active after the rainy season. And they discovered that curvy roads and sections far from human settlements saw the most accidents, while areas that ran through denser forests or had straighter paths tended to be safer for both animals and people.

The researchers didn’t stop at counting the accidents. They wanted to understand where and why they were happening. Using maps, field surveys, and computer models, they identified three major danger zones on that road. These hotspots were responsible for more than 60% of all wildlife collisions. They also learned that accidents happened more often in the autumn, when animals are more active after the rainy season. And they discovered that curvy roads and sections far from human settlements saw the most accidents, while areas that ran through denser forests or had straighter paths tended to be safer for both animals and people.

WaNPRC Director Dr. Deborah Fuller today welcomed Dr Raimon Duran-Struuck as a core faculty member of the Washington National Primate Research Center. Dr Duran-Struuck is the Chair and a Professor in the UW Department of Comparative Medicine (DCM).

WaNPRC Director Dr. Deborah Fuller today welcomed Dr Raimon Duran-Struuck as a core faculty member of the Washington National Primate Research Center. Dr Duran-Struuck is the Chair and a Professor in the UW Department of Comparative Medicine (DCM).