You can trace a direct line between the recent headline-grabbing FDA approval of HIV prevention and treatment drugs to research at the Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC). And the history of WaNPRC’s involvement in fighting the HIV epidemic goes back years.

You can trace a direct line between the recent headline-grabbing FDA approval of HIV prevention and treatment drugs to research at the Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC). And the history of WaNPRC’s involvement in fighting the HIV epidemic goes back years.

While media coverage of Yeztugo, formally known as lenacapavir or Sunlenca, is understandably focused on the successful human trials, it might not have gotten to human trials at all were it not for animal studies, including those done at WaNPRC.

Yeztugo is a promising tool for many patients. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 1.1 million people in the U.S. are living with HIV. Even though fewer people are getting HIV each year — with about 36,300 new cases in 2018 and 31,800 in 2022 — the disease still hits certain groups harder than others. Experts think one big reason HIV is still a problem is because many people who could benefit from medicine that prevents it (called PrEP, or Pre–Exposure Prophylaxis) either don’t know about it, can’t easily get it, or forget to take it every day. So, a twice-a-year shot has the potential to boost the longstanding effort to reduce HIV rates over the coming years. While Yeztugo is for PrEP, Sunlenca is used as a treatment of HIV in combination with other medications. How these drugs got to this point is where WaNPRC researchers and monkeys enter the picture.

In lieu of a cure, the focus has been on using PrEP to halt transmission between people.

In the mid-1990s, Dr Che-Chung Tsai, a WaNPRC affiliate scientist, showed that an experimental drug, called tenofovir, when administered to pigtail macaques just before or after exposure to SIV (a virus very similar to HIV that causes AIDS in nonhuman primates) study completely protected the animals from infection without adverse effects.

This success led Gilead to develop the licensed version of tenofovir (called Truvada) that has been now used for two decades in the US and worldwide to reduce HIV transmission. This success led Gilead to pursue more options. Among those was lenacapavir, now known by the brand name “Yeztugo and Sunlenca.”

Before Yeztugo and Sunlenca could be tested in humans, it had to be first tested in petri dishes to show it could neutralize the virus. Years of work led to optimizing the drug’s ability to neutralize the virus in a dish. But showing a drug works well in a dish is not enough. To determine the feasibility of using this drug in people, essential studies in nonhuman primates were needed to determine the dose of drug needed to block infection in the body, to determine where the drug goes in the body and if it was safe. This is where WaNPRC once again enters the picture. Dr. Tsai’s early work with Truvada showed the value of the pigtail macaque in predicting the success of a treatment for human use and this led to researchers testing this new drug to reach out to WaNPRC to support this research by providing pigtail macaques for their crucial preclinical study prior to advancing this drug to human clinical trials.

“Female pigtail macaques are preferred for studies to develop antivirals and vaccines to prevent vaginal and rectal transmission of HIV due to their close similarity to both males and females. In particular, female pigtail macaques exhibit the closest similarity to the human female menstrual cycle and have played a crucial role for decades in studies of HIV transmission and prevention in women”said WaNPRC Director Deborah Fuller, who lauded the work leading up to this new drug.

But the work doesn’t end there. WaNPRC is continuing to support studies that aim to halt the spread of HIV. Dr. Rodney Ho, a WaNPRC affiliate researcher and professor in pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Washington pigtail macaques at WaNPRC is developing a different long-acting HIV drug combination, intended to provide even longer lasting HIV viral suppression. His innovation recently entered human clinical trials in collaboration with WaNPRC’s Associate Director of Research, Dr. Kristina Adams Waldorf.

He touts his contributions in establishing the methods were used to enable the ability of PrEP to directly improve human health. With antiviral drugs preventing transmission, Ho said, “life expectance greatly increases. There’s no public burden on health care costs and a higher quality of life for patients who can live out their normal lives.”

The story of Yeztugo and Sunlenca is a powerful example of how early-stage research at WaNPRC laid the foundation for medical breakthroughs that can saved millions of lives. The WaNPRC’s contributions underscore the role of nonhuman primates in translating discoveries into real-world solutions. WaNPRC is committed to this mission and will continue to play a key role in developing the next-gen treatments to prevent and treat HIV and to improve the quality of life and health of people.

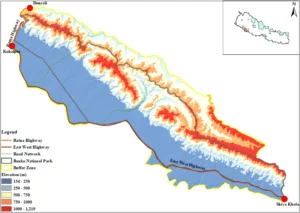

The researchers didn’t stop at counting the accidents. They wanted to understand where and why they were happening. Using maps, field surveys, and computer models, they identified three major danger zones on that road. These hotspots were responsible for more than 60% of all wildlife collisions. They also learned that accidents happened more often in the autumn, when animals are more active after the rainy season. And they discovered that curvy roads and sections far from human settlements saw the most accidents, while areas that ran through denser forests or had straighter paths tended to be safer for both animals and people.

The researchers didn’t stop at counting the accidents. They wanted to understand where and why they were happening. Using maps, field surveys, and computer models, they identified three major danger zones on that road. These hotspots were responsible for more than 60% of all wildlife collisions. They also learned that accidents happened more often in the autumn, when animals are more active after the rainy season. And they discovered that curvy roads and sections far from human settlements saw the most accidents, while areas that ran through denser forests or had straighter paths tended to be safer for both animals and people.

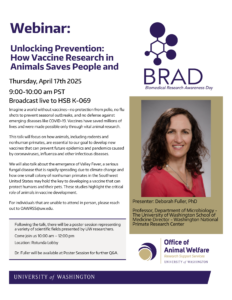

WaNPRC Director Dr. Deborah Fuller today welcomed Dr Raimon Duran-Struuck as a core faculty member of the Washington National Primate Research Center. Dr Duran-Struuck is the Chair and a Professor in the UW Department of Comparative Medicine (DCM).

WaNPRC Director Dr. Deborah Fuller today welcomed Dr Raimon Duran-Struuck as a core faculty member of the Washington National Primate Research Center. Dr Duran-Struuck is the Chair and a Professor in the UW Department of Comparative Medicine (DCM).