WaNPRC’s Neuroscience unit has contributed four noteworthy advances in science in recent months, including a new discovery about color vision, advancements in how primate brains differentiate objects, and even how our brains help us chew and swallow food.

New findings from the lab of Core Scientist Dennis Dacey, PhD, are unraveling the complex circuitry of the human retina, where vision starts. His lab’s results suggest new pathways for color vision and emphasize the need for complete wiring diagrams of the human central nervous system.

Dacey mapped, cell-by-cell, the physical pathway that color signals travel through the retina. Before Dacey’s discovery, it was thought there were two color pathways: a red/green path, and a blue/yellow path. Dacey found that some cells carry both at same time.

“They’re re-writing the book on the retina,” said unit chief Greg Horwitz, PhD, praising Dacey, who is the most senior member of the unit. “The part of the retina that Dennis is focused on is the part that resolves fine details. And it’s the part that fails in macular degeneration. It is usually thought of as a high-resolution version of the rest of the retina, but Dennis’s work is showing it’s actually highly specialized.”

Horwitz himself also recently published a paper with Research Associate Professor Robi Soetedjo, PhD, announcing new findings about how specific cells in the brain control certain eye movements known as saccades

Horwitz and Soetedjo used a laser to stimulate Purkinje cells in the cerebellum of a monkey at the precise moment of saccade. They found that if the monkey looked in one direction, the saccade slowed. If the monkey looked the other direction, saccade went beyond the expected target, showing that they are not just two opposing functions

“It gives us a tool. If it works in eye movements, it might work for studying other cerebellar functions including movements of the arms or body,’ Horwitz said

Their findings were published in the Journal of Neuroscience in February.

Four months later, Anitha Pasupathy, PhD, and her ShapeLAB team published a paper in the same journal, advancing our understanding of how neurons in a primate’s brain process objects that are part of a group.

Pasupathy’s lab showed primates a target image – let’s say a yellow triangle – and compared how neurons in the brain’s visual cortex responded when the triangle was surrounded by similar versus dissimilar objects. From these measurements, they discovered that the brain could differentiate the target object more readily when it stood out from the dissimilar objects.

“What that tells us is the brain has a way of suppressing activity of things that are similar,” Pasupathy said. “For efficiency, the brain may pool similar objects and encode them together. But that center yellow triangle is special when it’s surrounded by dissimilar objects, and maybe it’s something of interest to the visual system.”

She said the next step will be tests to see if monkeys can pick out objects they see, and whether that corresponds to what neurons are telling the researchers.

Fritzie Arce-McShane, PhD, published a paper in Nature Communications (and recent pre-preprints here and one on age-related changes here) furthering our understanding of how the brain drives the muscles involved in chewing and swallowing in ways that could lead to new interventions that could help patients having trouble with these vital functions due to aging or brain disease, such as Alzheimer’s Disease.

“How the brain controls chewing and swallowing is very much understudied and the big challenge in studying this is tracking the position and shape of the tongue inside the mouth when we chew and swallow,” Arce-McShane said.

Using a combination of x-ray technology with sensors and machine learning-based analyses of brain signals, her studies have shown that when primates eat, there is robust information in the primary motor cortex and the somatosensory cortex that define the 3D direction of tongue movements, and also the tongue shape. “That hasn’t been shown before. The tongue’s shape has importance in positioning the food and preparing it for swallowing,” she said. Changes in the pattern of tongue movements have been observed with aging and Arce-McShane expects that these changes will also be reflected in the brain signals.

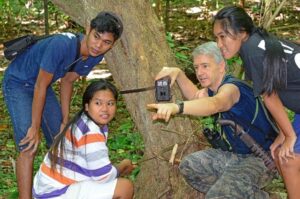

The Neuroscience unit at WaNPRC is dedicated to supporting state-of-the-art research in nonhuman primates both inside and outside the WaNPRC. Nonhuman primates have and continue to play a critical role in advancing our understanding of how the human brain works due to their close similarities in structure, physiology, and genetics to humans. Using nonhuman primates, the Neuroscience Unit at WaNPRC is at the cutting edge of advancing our understanding of the function of the human brain and developing new treatments for a wide range of neurological disfunctions. You can find more information on the Neurosciences Unit and the exciting research of its 23 core and affiliate faculty here.

Increasing investment and support for neuroscience research involving monkeys is critical to realize our hope for advancing human health and reducing suffering for millions of people confronting diseases like Alzheimer’s, bipolar dis- order, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia. So argues Dr. Michele A. Basso, core scientist in the Neuroscience unit of the Washington National Primate Center.

Increasing investment and support for neuroscience research involving monkeys is critical to realize our hope for advancing human health and reducing suffering for millions of people confronting diseases like Alzheimer’s, bipolar dis- order, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia. So argues Dr. Michele A. Basso, core scientist in the Neuroscience unit of the Washington National Primate Center.