A recent workshop put on by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) called for more funding for research leveraging New Alternative Methods (NAMs), and less for animal models. The Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC) strongly supports the development of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in biomedical research to refine, reduce and replace animal testing. And as the director of WaNPRC, I think it’s important for the public to understand how we get there.

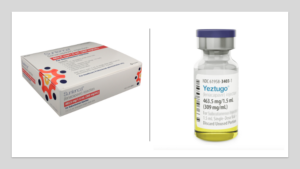

There is no doubt that research using animal models has an enormous impact on human health. It has unlocked important insights into the underlying biologic processes that impact our health and causes of disease and has made possible the development of new medicines that are now preventing and treating diseases and saving countless human lives. Indeed, nearly every prescription medicine we have today can trace its success to research and testing in animals. The long-acting drug, Yeztugo (Lenacapavir) that was recently approved by the FDA to prevent HIV infection is just one example that can trace its origins to a pivotal study in nonhuman primates at the Washington National Primate Center that provided the first in vivo proof that administering antiretrovirals pre-exposure could prevent HIV infection.

Scientists take seriously their responsibility to ensure that the animals they use in their research to advance knowledge while also refining methods to minimize pain or distress. They are also motivated to develop new methods to reduce the number of animals needed, or replace them entirely, to gain that knowledge. Researchers using animals are deeply committed to these principles of the “3Rs”, and they have, and will, continue to play a central role in advancing NAMs to achieve these goals.

Nonhuman primates (NHPs) comprise an extremely small percentage (<0.5%) of all animals used in biomedical research but they serve an outsized role in enabling the advancement of many areas of research due to their very close biological and physiological similarities to humans. To date, there are still no better alternatives than the NHP, including other animals or non-animal methods, to model many complex biological functions in humans including the central nervous system, cognitive function, the immune system, ear and eye function, fertility and the female reproductive system, long-term toxicity and systemic metabolism, to name just a few. Scientists have learned much about diseases, prevention and treatments from NHPs and many of these findings have led to new medicines in humans. Using animals that are so like humans, however, naturally raises ethical concerns which is why NHP research is highly regulated and requires an extremely high bar to justify their use. And it’s also why NHP researchers have, for years, worked to find ways to refine, reduce and replace their use in research. For example, at WaNPRC:

- Our primate behaviorists developed a novel positive reinforcement training method that encourages NHPs to work cooperatively with researchers. In doing so, there is little or no stress enabling more accurate evaluation of their response to stimuli and experimental drugs (refinement).

- Our infectious disease and gene therapy scientists have developed and validated several highly reliable in vitro and ex vivo NHP and parallel human models to screen new medicines for safety and efficacy prior to testing them in NHPs. This has significantly reduced the numbers of NHPs needed per experiment, from approximately 30-80 10+ years ago to < 20 today (reduction).

- Our neuroscientists are developing highly innovative algorithms for AI prediction of brain function including pioneering work that defines how neural activity controls movement (i.e. “decoding of the brain). We are also using AI to create a neural network that associates images NHPs see with a response to those images to develop a “digital twin” of a real neuron. Training AI models is not possible without collecting real-life data from NHPs as the closest model to humans to accurately measure brain activity. The long-term goal is to enable hypothesis testing of complex brain functions without the need for animals (replacement).

As a result of these efforts and many other examples like this at WaNPRC, since 2018, we have reduced the number of NHPs required to support research projects by over 30% while increasing the number of research projects and discoveries. Given our shared goal and motivation to reduce the reliance of biomedical research on animals, scientists and vet staff at WaNPRC strongly support the mission that the NIH and FDA announced in this workshop to reduce animal testing through the development of NAMs.

The success of NAMs will depend on high standards for validation against established animal models. While research in NAMs is rapidly progressing, moving too quickly creates considerable potential risk. To replace animals, rigorous testing must be done for each new alternative to ensure it can accurately model patient safety and provide regulatory confidence. As promising as these tools are, they still vary widely in their maturity, standardization and predictive power. While many are being used by researchers to complement and enhance what we can learn from animals and their ability to predict outcomes in humans, most are not yet ready to completely replace animals. Enthusiasm for innovation in NAMs should not outpace the careful validation necessary to protect patients and the need to preserve the public’s trust and integrity in the drug development process.

In summary, the use of animals, including nonhuman primates, remains necessary for many types of biomedical research. We applaud the FDAs decision to phase out mandatory animal testing for drugs when there is clear validation and high confidence in the alternative. At the same time, replacing and reducing animal testing must be guided by rigorous standards and made on a case-by-case basis. This will require a strong partnership with scientists who do animal research and careful, evidence-based roll-out of policies. This will require increased investment not only in NAMs but also continued investment in animal models, especially for complex endpoints that require a deep understanding of underlying mechanism, many of which have yet to be discovered and where the initial insight may only be possible through animal studies.

A careful phased approach is needed that includes fostering collaborations and trust with researchers, clinicians and veterinarians who can help develop clear guidelines, criteria and confidence in the reliability of any new technologies. The future of drug development will depend on this, and we welcome the opportunity to work with the NIH and FDA on this mission.

Deborah H. Fuller, PhD

Professor, Department of Microbiology | University of Washington School of Medicine

Director | Washington National Primate Research Center

I applaud the Oregon legislature for tabling a misguided bill that would have shut down the Oregon National Primate Research Center. The

I applaud the Oregon legislature for tabling a misguided bill that would have shut down the Oregon National Primate Research Center. The  You can trace a direct line between the recent headline-grabbing

You can trace a direct line between the recent headline-grabbing

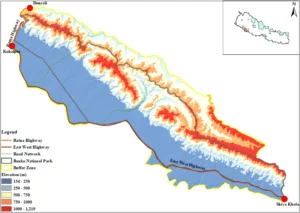

The researchers didn’t stop at counting the accidents. They wanted to understand where and why they were happening. Using maps, field surveys, and computer models, they identified three major danger zones on that road. These hotspots were responsible for more than 60% of all wildlife collisions. They also learned that accidents happened more often in the autumn, when animals are more active after the rainy season. And they discovered that curvy roads and sections far from human settlements saw the most accidents, while areas that ran through denser forests or had straighter paths tended to be safer for both animals and people.

The researchers didn’t stop at counting the accidents. They wanted to understand where and why they were happening. Using maps, field surveys, and computer models, they identified three major danger zones on that road. These hotspots were responsible for more than 60% of all wildlife collisions. They also learned that accidents happened more often in the autumn, when animals are more active after the rainy season. And they discovered that curvy roads and sections far from human settlements saw the most accidents, while areas that ran through denser forests or had straighter paths tended to be safer for both animals and people.

I recently returned from Washington, D.C., where I was pleased to see something uncommon right now: bipartisan support for biomedical research. I want to applaud it and call out what WaNPRC is doing to continue to deserve that support.

I recently returned from Washington, D.C., where I was pleased to see something uncommon right now: bipartisan support for biomedical research. I want to applaud it and call out what WaNPRC is doing to continue to deserve that support.